there’s nothing a writer loves more than reading. about writing. we got your readin’ and writin’ right here.

there’s nothing a writer loves more than reading. about writing. we got your readin’ and writin’ right here.

Category Archives: literature

novella trifecta

we are pleased to announce that the third Six Sisters novella,

Quality of Light, is now available. So, what are you waiting for?

fiction valentine 1.4

Love. It’s everywhere. Some would even venture to say that if you haven’t found it, you’re not looking.We don’t know if that’s true. We do know that sometimes fictional love is better than no love at all.

Love. It’s everywhere. Some would even venture to say that if you haven’t found it, you’re not looking.We don’t know if that’s true. We do know that sometimes fictional love is better than no love at all.

Excerpted from “Jesus, Mary, Buddha”

Over warm olives and crusty sourdough, Helen learns that Nick’s third wife parked her Range Rover at the edge of town on the banks of the Snohomish River and washed down a handful of pentobarbital with a bottle of flinty Oregon pinot gris.

It was his first year of mourning and he still hated her and loved her in ways he hadn’t yet explored. “I don’t know how I can do better than that,” he told Helen one night. “I mean fucking look at her.” He gestured toward a framed photo of them on his living room mantle. “She’s gorgeous.”

On Earth Day they up-cycle a pair of antique windows and build a table out of them. Later, they eat salmon with their fingers, straight out of his backyard smoker. After dark, they sit in deck chairs in the garden and watch shooting stars. Eight weeks into their affair, she drives home through the city streets late at night with the windows down, with air warm as a lover’s breath sliding up her arms, through her hair. The rhododendrons are in bloom. The azalea, lavender, chives, strawberries, raspberries, pear, five kinds of apple, chestnuts. Even at 11 pm, there are couples walking, cyclists peddling down the quiet evening streets in thin cotton dresses, short sleeves. It is evident that even in the dark, they are sucking the juice out of the first days of summer, taking shy steps toward the grilling season.Through the car windows, Helen Okabe breathes in the perfume of lilac.

For his birthday she gives Nick an anatomically correct chocolate heart spiced with habanero pepper. He makes his signature clams and beer. Afterward, he builds a fire in the backyard firepit and they recline on deck chairs, watching the sky. He talks about his men’s group, about getting in touch with his feelings.

“I’ve been wondering,” he begins. “What if I’ve been sabotaging relationships my whole life?” Unlike so many middle aged men, Nick is messed up on love and he knows it. To his credit, he is actually trying to unpack that baggage.

Helen sucks an ice cube and lets the water slide down her throat. “I was just wondering that myself,” she says. She has. She has been doing her spiritual inventory and counting up the number of times that, when the going got tough, she got gone. She was up to four. It wasn’t pretty.

“I think I have intimacy issues,” he says.

“Wait,” she replies. “You said you and Reina were simpatico. You were married ten years. You renewed your vows every spring for God sake. That sounds awfully intimate to me.”

“Nah,” Nick waves the idea away. “That was only appearances. I checked out after two years, if I’m honest about it.”

Appearances, her Zen master said, not only fool, you they aren’t even real. Helen still hasn’t wrapped her head around that one.

She offers the only solace she has, something from a piece of research she is working on. “The top five fears of most people are public speaking, followed by flying, heights, fear of the dark, and intimacy.” She counts them off on the fingers of her hand and refrains from adding that following this list, the fears continue with death, failure, rejection, spiders, commitment.

“That can’t be right,” Nick says.

“It’s from a university study,” she replies.

“I would say fear of intimacy is number one,” he continues.

“People are scared to death of intimacy. Just think what it means if you are right.”

“I am right.”

“If you are right, and I’m not saying you are, it means people would rather sleep with strangers than speak in front of a crowd of them.”

“It doesn’t mean that at all.”

“People are more afraid of emotional honesty than talking,” he says. “Look,” he says, pointing to a light moving across the night sky, “a satellite.”

It is a clear spring night and the sky is shy of clouds and the moon is new so they have space to shine. “Anyway. That’s my story, and I’m sticking with it.”

(c)

Cynthia Gregory

fiction valentine 1.2

we’re sharing stories of love this week because love is so big and one day is so small. today we’re starting a little catalog here. sort of . decide for yourself.

we’re sharing stories of love this week because love is so big and one day is so small. today we’re starting a little catalog here. sort of . decide for yourself.

excerpted from “ALMOST CANADA”

She moves up the aisle toward the dining car to pass the time until the train resumes its forward motion. At the narrow counter, she takes a stool beside to a dark haired man, orders a glass of ginger ale. The man is working on a burger. He shifts his eyes toward her, measuring. His hair is glossy, black as a raven feather and close-cropped above his collar. One long border of bristled hairs makes a ledge over his eyes, his nose hooking sharply over a pretty mouth.

“Gotta love ther rail, right?” he said. He hitches a smile in Antonia’s direction.

“Excuse me?”

“One goddam delay en anerther,” he explains. There is a mole on his neck, just behind his left ear that moves as he chews and talks. It is the size of a grain of rice.

The man tilts over the counter toward his food, hooks his arm around his plate forming a border between his fried potatoes and Antonia. He is not a small man, or bird-like, but his movements suggest the motions of the ravens that inhabit the tree outside of her office window. Antonia watches the bubbles rise in her glass of pop, thinks about what she knows about ravens, which begin to court at an early age, and then mate for life. In part of the mating process, a male raven will demonstrate intelligence and a willingness to procure food or shiny objects. Egg laying begins in February so courting must take place in early to mid-January.

Antonia is a vegetarian more by disposition than philosophy. This is to say, she will eat meat to avoid hurting her neighbor’s feelings if invited for dinner. In a restaurant, she will select venison if the side dishes or greens are inferior. The man makes the hamburger vanish, chunks at a time, washing it down with pale beer. When he finishes, he wipes the corner of his mouth with a large, square thumb. His eyes rake her face, drop to her sweater. “Wheer ya headed? Goina Canada?”

Antonia stares at the chip bisecting his incisor, wonders what it would feel like to run her tongue over that rough surface. Her mouth forms a watery smile. Common ravens are highly opportunistic. “Almost,” she says, leaving money for the pop and spinning away. “I’m going to Almost Canada.”

She is mutable, an object of desire. She is a screen upon which projections are made: a bold maiden, a volatile spinster, the girl with the long grey skirt and the blouse with pearl buttons.

The man swipes twin circles of pickle from his plate and drops them on this tongue like holy wafers. He watches the twin moons of her rump as she moves away.

Antonia returns to her seat to find that in her absence, the pair of facing seats across the aisle has been occupied by three girls, sisters, traveling on their own. The oldest, a teenager with sleek black hair, presses out text messages on her phone, while the two younger girls share a laptop computer and review the Facebook posts of friends. They are fundamentally beautiful in the way of youth and by heritage; their ancestors inhabited these coastal meadows centuries before Europeans arrived with their fur trades and their thirst for whale oil. Antonia peers beneath her own lashes at the contrast between their dark hair and their alabaster skin, the curve of their lips above the slow arcs of their chins.

She feels a rush of gratitude for such vigorous charm, such tender virtue. As the train begins to slow for the next station, the oldest, the managing sister, switches from texting to making a call to determine at which city the trio will depart the train. The girl says It’s me. We’re coming to the station. Do we get off here or the next one? Antonia wonders how there can be confusion about the care of beautiful dark-haired girls. Mom, the girl says. Mom, please don’t yell at me. I just need to know, which station? And like that, a picture develops; the first one, the responsible child, the good girl. Antonia’s heart breaks a little for these sylph.

(c)

Cynthia Gregory

fiction valentine 1.1

here is an except from a story I wrote called, “Not My Suicide.” It’s about how nothing is what it seems: not love, not time, not nature.

Some people, those who are either marginally motivated or marginally skilled, don’t manage to close the deal the first time and try again, compulsively. Psychologists say that some people go at it up to fifty times before actually making it. Strangely, you could say that one success in fifty is respectable. One hundred in-vitro attempts will statistically result in eleven babies. Edison, who was afraid of the dark, made three thousand attempts to create the light bulb before he succeeded. It’s a matter of perspective.

Finally, Viola had had enough. “Can we talk about something else?”

Marina straightened her spine, pointed toward the light fixtures overhead. “Global warming.”

Bibi choked on her biscotti. “Are you off your meds?”

Marina wagged her chin. “We’re murdering the planet.”

“Calm down.”

“Don’t mother me.”

Peace begins with me, I thought. Peace begins with me. “Please, ladies.”

“She’s in denial,” Bibi insisted. “A victim of the liberal media.”

“Liberal — are you nuts?” Marina was not having it. “They’re saying that global warming is a myth, that alternative energies cost too much.”

“Geez Louise, don’t have kittens. You want an almond cookie?”

“I don’t want an effing almond cookie. I want rain forests and tree frogs and glaciers.”

“You’ve never even been to a glacier.”

Water pooled in Marina’s cerulean eyes. “Scientists in Norway are finding industrial flame retardant in whale blubber.”

“Stop.”

“It’s true. Poly-something –they use it to make furniture, clothing, computer chips.”

“How did it get in the whales?”

Marina folded Bibi’s hands in hers, squeezed lightly. “Through the water table, Beeb.”

“What? That doesn’t even make sense.”

In the ‘twelve simultaneous versions of Now’ world view, it is possible to be both dead and alive at the same time, both here and there. As if our so-called lives aren’t complicated enough.

(c)

Cynthia Gregory

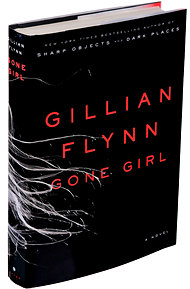

give me fiction. give it to me now.

The only way the books we review could be better is if they were ours.

We’re working on that.

In the meantime: Read this review. Buy this book. Support the arts!

one loyal group

Pam Lazos

Chapter Seventy-Six

Hart sat on the bed in his hotel room reading the newspaper behind closed eyelids. Two sharp raps on the door startled him awake.

“Hold on,” Hart called. He rubbed his entire face with one hand before rising to look through the peephole.

“What the — ?” Hart said, throwing the door open.

Bicky held up a hand to silence him. “May I come in?”

Hart stepped aside to allow Bicky ingress. Bicky headed straight to the window.

“I’ve been calling you all day,” Hart said. “What the hell are you doing here?” Hart grabbed two beers out of the mini-fridge, popped the tops and set one down on the window sill next to Bicky. “And what happened to your hand?”

Bicky appraised the appendage as if it were an alien species, but said nothing so Hart switched topics.

“I’ve secured financing. But it means I have to sell out. Completely sell out. Every last stock certificate.” Hart gave this information some time to sink in, but Bicky didn’t answer, just stared out the window, his face glued to the view. “Look, I know what that could do to you…to the company. And I’m not trying to undermine you, Bicky, so if you can get the money together….”

“I spent the whole day with the kids.” Bicky stood as still as Billy Penn atop City Hall Tower, staring out over the Delaware, watching the ships come in. “She came back nicely, didn’t she?” he said, nodding toward the river. “Not even a trace of the spill is visible to the naked eye. And it’s only been what? Two months? He picked up his beer and raised the neck to tap Hart’s own. “To the healing power of nature.” Bicky took a seat on the window sill and turned to Hart, his entire body engaged.

It was the atypical nature of the gesture that made Hart uneasy. “I’m guessing you didn’t come here to talk about nature.”

Bicky shook his head. “I was wrong. Too many times over these years I’ve treated you with less than the respect you deserved.” Bicky picked up the beer, but did not drink. “You’re a fine engineer, and a fine son-in-law. Probably the best I’ve ever seen in both categories.” He set his beer down and stood up. “I just wanted to tell you that.”

Hart stared at Bicky, mouth agape. In the ten years he’d known his father-in-law, Hart had received more than his share of the booty for a job well done: new cars, six-figure bonuses, vacations in exotic settings, even a boat once, but this one small comment, mixed with confession, was the most profound and heartfelt gesture Bicky had ever made. Perplexed and more out of sorts than when Bicky first walked in, Hart stood up, too.

“Thanks,” he said. He looked at Bicky queerly for a moment until Bicky’s words sunk in. “The kids? I guess you’re talking about my kids?”

“Very fascinating family. I’ve been thinking about this all day and I’m prepared to make a deal that benefits everyone. Truly benefits everyone.”

“I’m listening.”

“Tomorrow. Let’s meet at the Tirabis’ in the morning. Say ten?”

“You want to give me a glimpse into the future?”

“The thought struck me that you could benefit from an existing facility, not just for refining purposes, but for transport. We have pipelines all over the country bringing raw crude into our refineries. What if we reversed the process? Instead of pumping to us, we send the finished product, the stuff you distill from trash, away from us to be either sold or further refined around the country. We can run this without the additional capital and I predict….”

Hart’s smile was so wide, Bicky stopped in mid-sentence.

“What?” Bicky asked.

“Had you given me the chance on the phone that night…”

“Oh. You already thought of that, is it?” Bicky smiled, his trademark half-smile. “Thanks for humoring an old man.” Bicky patted Hart on the back and walked to the door. “Tomorrow.”

“The Tirabi kids know we’re coming?”

“Yes.” Bicky stood face-to-face with his son-in-law, his hand on the doorknob. “They are one loyal group. They wouldn’t deal with me at all until you were at the table. You should be proud of that. The ability to engender loyalty is a lost art.”

Hart smiled, but couldn’t formulate a response because of the large boulder in his throat. Bicky squeezed Hart’s shoulder and shook his hand at the same time.

“See you tomorrow, son.”

to be continued. . . .

copyright 2013

sister::sister

sometimes you love your sister. sometimes you don’t.

sometimes love and denial get all mixed up together.

orange you glad

a guide to writing

Cynthia Gregory

The beauty of the journaling process is that it can be simple or it can be complex in a way that reveals itself as a personal, daily, moment-by-moment choice. What enriches the journaling experience (if you’re willing), is variety, is texture.

Imagine eating the same salad every day of your life. You can argue that rich, leafy greens provide minerals and nutrients essential to optimum health. You can also argue that periodically a bowl of thick, smooth, mocha fudge ripple ice cream has the capacity to transport you to your happy place, to a time when summer afternoons sprawled under the shade of a leafy maple counting squirrels in the branches above was the most important assignment of the day. Variety. Texture. Sometimes the best you can do is bolt down a protein bar on the run. Other times, you want to immerse yourself in the sensual, primitive pleasure of a feast of market fresh produce, a plate of pasta cooked perfectly al dente and smothered in an aromatic sauce of eggplant and basil and roasted peppers.

Sometimes your journal is where you lock in and unload your thoughts of the day, the dramas of your life, your hopes for your lover, your future, your Self. Sometimes your journal is a train and each entry is a station. Sometimes the station is the destination, sometimes it’s the jumping off place, the place where adventure begins. Neither place is superior to the other, it is enough that they are what they are. However, this journaling assignment is about the jumping off place, about getting to the end of everything you know, standing poised on the edge with your toes hanging over, a yawning expanse of never been-there-but-open-to-the-possibility. This is the station where you disembark the train and immediately jump into a waiting cab and vanish into the landscape.

This drill can be accomplished using any number of ordinary household items, a hammer, a clothes pin, a plum, or in this case; an orange. Choose any orange you like; choose a sweet as candy Clementine, sometime that rests in the palm of your hand like a tiny jeweled box. Or select a bouncy navel with its nubby button and thick peel. A secretive blood orange, interior cloaked in a plain wrapper. Don’t agonize over the choice; one is as good as the other. Remember, this isn’t about the orange. The orange is only the station platform, the way in.

Remember before, when I suggested that you enter a room and stay there until you’ve achieved the mission of full emotional disclosure? Of going to that place where you blink into the darkness, open your ears to the music of the silence, of letting the air move over the surface of your skin and registering the sensation with words on a page? This is more of that. It is probably easier to make this a timed writing, because the level of difficulty might otherwise persuade you to pitch in the towel long before you get to the juicy bits, the place where you discover something new. With a timed writing, you are not focused so much on the content of the writing, as in the endurance of the time.

A funny thing happens with the timed writing exercise. Generally, you take off with great alacrity, writing everything you know about a subject. Interestingly however, if the time is of a challenging length, the writer finds that she runs out of known material in a relatively short period of time. She finds she has a surplus of minutes, and a surfeit of words. How does this happen? It is a trick of the mind. No matter, this is where it gets interesting.

Find a quiet place to write, free of distraction. Set a timer and begin. First, pick up your orange, close your eyes and inhale its tart-sweet fragrance. Really smell it. Roll it over the skin of your throat, across your chest. Toss it from one hand to the other, examine the surface of the peel, each dimple, every blemish. Experience the orange with your senses as fully as possible, then set it down nearby and begin to write. You may begin with a literal description, and you may actually get a paragraph or two from the physical presence of the fruit, the weight of it. Then what? Then we meet the cousins of “reality” namely imagination, and memory, we are about to move beyond what is and approach what if.

Here are possible ways to go from here. Write about:

- Your first memory of citrus fruit

- The girl you knew who smelled like orange blossoms

- The texture of the creamy white pith beneath your fingernails when you peel it

- the camping trip you took where after three hours of steady hiking you stopped by a creek and tore the flesh of a tangerine and drank the pulpy juice with absolute gratitude for the miracle of orange-ness the way the skin split, revealing the color of a ripe sunset on a honeymoon cruise and dancing under a full moon and the feel of sin on skin, of succulent, sweet juice dripping down your chin at dawn

You see -it’s not really about the orange. At least, not necessarily so. The orange is a trigger; it is the beginning place that has the power to transport you to another time and place for the duration of whatever time you establish at the beginning of the writing.

It’s important in a timed writing to stick with the intended time. If you establish a fifteen or twenty minute limit, stick with it. If you find you run out of preconceived ideas of what you think you should be writing about, stick with it. Let go of the idea that you choose the words to commit to the page. Let the words choose you. Let the idea pick you up and shake you loose of everything you thought it should be. When you come to the place where your treasure chest of “good” ideas is empty, be patient. Be calm. Wait. Let the ideas float into your mind and don’t judge them, don’t try to shape them. Write them down. Let the ideas flow and allow the gentle waves of the stream of consciousness lap gently at the shores of your mind. This is the place where new ideas are birthed. This is the place where imagination and memory merge, form something new, and your job is to write it down. It sounds simple; it is. It sounds difficult; it is not. All you have to do is be willing to let your subject: the orange, the plum, the paper clip -reveal a story to you, and then your job is to introduce it to your journal.